Somalia in the age of the War on Terror: An analysis of violent events and international intervention between 2007 and 2017

Christopher D. Zambakari and Richard Rivera

Abstract: This study sought to investigate the geographic location and frequency distribution of three event types – violent events, nonviolent events, and events characterized by riots and protests – and the distribution of political and military events and death rates by region. We provided an assessment of various international interventions in Somalia between 2007 and 2017. Our results showed that violent events (N = 17,539, 86.9%) were by far the most common event type, followed by nonviolent events (N = 1,372, 6.8%), with riots and protests accounting for just N = 1,278 or 6.3% of total events. We found that almost one half (48.7%) of the events involved political or ethnic militias, and over 42.95% of events involved rebel forces, with slightly less than this accounted for by the government (40.2% of events) and 29.4% of the events involved civilians. The northern and central regions of Somalia registered the lowest number of events and fatalities, with most violent events and fatalities occurring in the southern regions. There was a burst of fatalities in 2010, and a steady increase in death rate from 2011 until 2017. External intervention has not halted this violence; instead, intervention has led to internal division in Somalia by subverting power dynamics, encouraging political polarization and radicalizing the insurgency and distribution of power, while lacking the resources and political will to sustain the preferred winning faction.

Keywords: Terrorism, peacekeeping, counterinsurgency, African Union, Somalia, state-building, conflict data

I. Introduction

The international community has been concerned about violent events and the impact of violence on the civilian population in Somalia for several years. This study investigates the geographical location and distribution of three types of events: violent events, nonviolent events, and events characterized by riots and protests. The distribution of fatalities in the general population and death rates by administrative region also are examined. An overview of political developments in Somalia is provided and the impact of various interventions in Somalia between 2007 and 2017 is assessed.

II. External interventions in Somalia

Political instability in Somalia has led to several external military and security interventions in the country, notably the United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM) (1993–1994), Ethiopia’s military intervention in Somalia (2006–2009), The African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) from 2007 to the present, and unilateral interventions by the United States as part of the War on Terror after the September 11, 2001 attacks (Hesse, 2014; Hirsch, 2018; Malito, 2016; Menkhaus, 2004). There have been interventions by Kenya, Ethiopia, and later Uganda (Hesse, 2014). The number of troops deployed has varied over time but has been significant. For instance, UNOSOM had around 22,000 troops, while AMISOM grew from its initial 7,200 in 2010 (Africa Research Bulletin, 2010), to currently six African countries deploying approximately 21,564 combat troops on the ground (Uganda with 6,223 troops, Burundi 5,432, Ethiopia 4,395, Kenya 3,664, Djibouti 1,000, and Sierra Leone with 850) (Hesse 2015). These numbers are likely to decrease slightly in the near future, as a recent U.N. resolution extended the AMISOM mandate but trimmed the upper limit of troop numbers to just over 20,500 (United Nations Security Council, 2018). The fatalities incurred by the peacekeepers have been heavy on contributing countries with 3,000 soldiers killed as of 2015, which approaches the 3,096 killed in all U.N. peacekeeping missions from 1948 to 2013 (Hesse, 2014: 350).

These interventions have all had to contend with a wide range of problems, including lack of a central government (since 1991), poverty and insecurity, the country emerging as a breeding ground for militant groups, and temporarily thriving piracy due to the power vacuum created by instability, and the ongoing war between clan-based fiefdoms.

This has been combined with the rise of militant groups like Harakat al-Shabab al-Mujahidin – commonly known as Al-Shabab, the militant wing of the Somali Council of Islamic Courts. Since 2006, the group has taken control of most of southern Somalia and waged several campaigns of destabilization in other parts of the country. It was also responsible for carrying out attacks in neighboring countries, including in Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda (Ingiriis, 2018; Vidino, Pantucci, and Kohlmann, 2010).

In a report for Saferworld, Suri’s assessment of external intervention in Somalia is mostly negative. He noted three key failures: (1) International actors have failed to underpin their military assertiveness with a coherent long-term peace strategy, (2) the military focus of defeating Al-Shabab has not succeeded; it has instead militarized society and locked international actors into a militarized approach to resolving the Somali conflict, excluding alternative approaches by key local stakeholders, and (3) the global counterterrorism agenda has reinforced a range of counterproductive outcomes, worked against local initiatives, and undermined efforts to build lasting peace (Suri, 2016: iv). Suri notes that, for example, the counterterrorism narrative has often served to harm ordinary Somalis more than it has diminished the capacity of Al-Shabab and, worse yet, there has been evidence that humanitarian assistance had been diverted to strengthen armed actors (Ibid., v). He also comments that there has been a lack of functioning oversight structure in the transitional government, a failure to understand the importance of clan membership in Somali society, and a focus on imposing structures from outside instead of building one from within.

A World Bank report noted that the root causes of Somalia’s conflict over resources and power were clannism and clan cleavages. The report also stated that traditional clan elders are “a primary source of conflict mediation, clan-based customary law serves as the basis for negotiated settlements, and clan-based blood-payment groups serve as a deterrent to armed violence” (World Bank, 2005: 9). It indicates that mixed relationships between the business sector and violence are at times a force for peace and stability, and at other times perpetuate violence. However, the report is silent on the negative role that an externally imposed intervention has played in the conflict and the mixed roles of international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and regional and international actors in the Somali conflict. Instead, it assumes that Somalia needs a centralized state, without questioning the history of centralized power in Somali society and historicizing the failures to build a stable government in the country.

The United Nations has been intermittently involved in the ongoing conflict in Somalia for several decades. The current U.N. role is through the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM), which is intended in part to aid in the democratic process and elections in Somalia as well as in part to aid the peacekeeping mission undertaken by AMISOM. It is noteworthy that even AMISOM – led by regional African states – has faced challenges operating in Somalia, and not just due to Al-Shabab. In part this is due to the relationship with the Transitional Federal Government (TFG). At first, the government irked family-based clans as a result of a perception that the government had infringed upon their territory in Mogadishu, making the situation more precarious; however, when AMISOM realized how the government had strained its relations with the clans, it restored power to the clans, which made the fight against Al-Shabab easier within Mogadishu (Roitsch, 2014; Escobar, 2011). It is clear that not only do AMISOM and the TFG need to fight Al-Shabab forces, but they must also provide support for civilians in need of aid, which remains a difficult task due to the lack of resources available to both AMISOM and the TFG (Anderson, 2016).

The international counterterrorism campaign has also had an impact within Somalia, given the relationship between Al-Shabaab and other Islamist extremist groups such as al-Qaeda. However, it has not always been clear whether Al-Shabab poses an imminent international terrorist threat (as opposed to a threat within Somalia), making it difficult to determine a proper course of action by external actors. Prior to 2009, the United States set up the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-terrorism, in which the United States allied with Somali warlords to fight al-Qaeda (Ibrahim, 2010). However, as the United States allied itself with the Somali government, drone attacks that kill civilians have unwittingly fueled anger against the Somali government. This has encouraged further rebellion and armed resistance, leading to more conflict and violence (Ibid; Malito, 2015; Suri, 2016).

An assessment of the effectiveness of the various U.S., U.N., and AU deployments to Somalia is often rather dispiriting. The results have not only been mostly failures, but also materially expensive. Hagmann’s study shows the impact of coercive intervention in Somalia in the periods between 1991–1995 and 2006–2016 in south-central Somalia. There have been recurrent negative relationships between external intervention designed for stabilizing the regions in Somalia and political settlements. Moreover, “coercive external state-building has encouraged violent attempts to produce a political settlement within the country” (Hagmann, 2016: 6). This is supported by Menkhaus’ research. He writes that “in virtually every instance, key actors took decisions that produced unintended outcomes which harmed rather than advanced their interests, and at a cost in human lives and destruction of property that continues to mount” (Menkhaus, 2007: 357).

Scholars have rightly pointed out the shortfalls of the current American approach to the War on Terror in other regions where the United States has carried out military operations. In the Horn of Africa, these have included a combination of, and reliance on: special operations without a coherent political strategy, the lack of effective diplomatic presence, little expertise on Somali domestic and regional politics, and a reliance on proxy countries for interventions on behalf of the United States, notably on Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda. The result has been a quasi-reproduction of Cold War-era proxy politics, with Ethiopia supporting the TFG, Eritrea lending its support to the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), also known as the Union of Islamist Courts (UIC), and Uganda and Kenya all taking part in military operations inside Somalia (Menkhaus, 2003).

Malito (2016), in her study of the peace initiative in Somalia and Somaliland between 1991-1995, concludes that the impact of externally imposed peace has failed. Moreover, the U.N.-U.S. external intervention has led to internal division in Somalia by subverting the power dynamic, encouraging political polarization, and radicalizing the insurgency and distribution of power while lacking the resources and political will to sustain the preferred “winning” faction (Malito, 2016: 1-24).

De Waal (2012) has observed that the international community’s preoccupation with uprooting terrorism and its insistence on establishing a western-style government (such as the TFG) is based on false assumptions: The belief that Somalia necessarily needs a highly centralized state, a preoccupation with suppressing the UIC and destroying Al-Shabab, and a failure to recognize the reality of the region and what already works (Elliot and Holzer 2009; Malito 2015). The central government cannot exist without foreign backing (AU, U.N., U.S.). This is supported by Suri, who shows that the focus on building a liberal state in Somalia has resulted in tensions and conflict. This externally driven approach, focused on reestablishing the national government’s centralized authority, has worsened instability and armed conflict, because it assumes that Somalia requires and desires a centralized authority and ignores the voices of the Somali people in the process (Suri, 2016: 35-37).

The last few decades have driven home a bitter lesson: Somalia is a hostile environment for an externally brokered and externally imposed peace. The various interventions have been based on the international community’s preoccupation with building a liberal nation-state, uprooting terrorism, and establishing a Western-style government in Mogadishu. However, attempts to militarily impose law and order and build a centralized or Western-style state have failed. Some scholars believe this failure has been due to a preoccupation with suppressing Islamic insurgents and preventing the insurgents such as Al-Shabab from gaining a stronghold in the Horn of Africa. The frequent changes in territory between AU-backed government forces and Islamist insurgents reflect both a failure to militarily defeat the insurgents and the financial challenges faced by the Somali AU-U.N.-backed forces (Ibid.). The inability to defeat Al-Shabab or sustain the cost of a perpetual peacekeeping mission raise questions about the viability of an international intervention in Somalia.

Ibrahim (2010: 283-295) argues that the very rise of Islamic insurgents such as Al-Shabab is partly a factor of the policy follies of regional and international players in Somalia. In addition, Somalia has been a field where other countries can demonstrate their own credentials. It has been argued that the justification among key contributing countries toward the AU peacekeeping mission was likely driven less by an interest in stabilizing Somalia than by attempts to deflect from domestic issues for some countries (such as Burundi); improve regional leadership credentials, for example by Ethiopia; and enhance participants’ international image and secure resources from key donors like the European Union and United States, as illustrated by Uganda and Djibouti (Elliot and Holzer, 2009). In many regions of Somalia undergoing conflict, external interventions have militarized local population groups, creating strong incentives for a small number of the Somali elites to remain involved in the conflict (Suri, 2016: 37-39).

According to De Waal (2012), the international community has failed to appreciate the fact that Somalia’s informal private sector is thriving and successful and has a major role in curbing violence. It has demonstrated remarkable adaptive capacity and resilience, with, for example, remittance transfers of US $700–800 million each year handled by Somali remittance companies. Elites have realized they can gain more from commerce than an unstable marketplace (Menkhaus, 2003; De Waal, 2012).

Somalia has suffered from another drawback of internationally mediated peace processes and an externally imposed peace, namely that external intervention has been prioritized over Somali-led internal processes, with only a narrow group of elites being engaged. One important lesson that the United States and those carrying out military operations in Somalia have yet to learn is the importance of the local context in building sustainable peace (Richmond, 2013). More than anything else, local rule matters greatly in matters of security and prosperity. Nowhere is this difference more pronounced than the differences between the northwest region of Somalia, Somaliland, and southern Somalia. One has developed into a relatively peaceful and democratically governed entity; the other has been ravaged by violent events. One has a viable self-sustaining government and the other is fragmented and controlled by competing clan-based groups (Harsch, 2017).

III. Micro-level analysis of violent events

The paper attempts to answer five research questions:

How frequently did different types of violent events occur in Somalia from 2007 to 2017?

How frequently were different actor types involved in violent events that occurred in Somalia from 2007 to 2017?

(a) What were the frequency of events in Somali regions from 2007 to 2017? (b) What were the frequency of violent events in Somali regions from 2007 to 2017?

Where were violent events concentrated in Somalia?

What were the annual event trends and death rates across the 11-year period?

One of the difficulties of studying violence is collecting data on conflicts from within a conflict environment. This challenge has motivated different agencies to adopt a variety of methods to collect conflict data, which has allowed more researchers to study violence using quantitative techniques. In recent years, social science research and conflict studies in particular have focused on a variety of factors that have been linked to the causes or effects of violence, or which can be used to categorize a conflict itself, including conflict outbreak, regime type, ethnic diversity and population composition, civil wars (Fearon and Laitin, 2003), and military coups d’état (McGowan 2006). More prominent in economic studies has been the study of the relationship of natural resources to conflict (Collier and Hoeffler, 1998). The use of quantitative techniques to study violence has led to development of matrices and indices to measure violence (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2016; Messner et al., 2014). Within these, geographically, African conflicts are increasingly represented in cross-national conflict event datasets.

One major development in the study of violent events has been the use of micro-level analysis. Frequently, micro-level data includes greater details about events: precise information about their location, geo-reference data, identification of the actors involved, and estimates of the severity or intensity of the violence.

Several factors have contributed to the growth of these micro-level and wider political event datasets. The first comprise the advent of technology and availability of information on the internet, as well as decentralization of information and reduction in the cost of gathering, coding, and storing data. The creation of specialized systems for automated coding, such as machine-assisted systems, has also facilitated the creation of event datasets. There has been increased interest and research focused on subnational variations in violence, and the involvement of non-state actors, making these some of the most active research areas in conflict studies (Ibid). This has all been accompanied by greater investment in institutions such as the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), and the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), which collect and disseminate data on conflicts (Schrodt, 2012).

The second characteristic of conflict event data is that researchers rarely collect primary data themselves. Instead, they use secondary data collected by agencies like ACLED and UCDP. Most of these violence datapoints rely on media reporting (Weidmann, 2016). News and media agencies seldom cover all events, and consequently media-based conflict event data suffer from selection biases that affect their accuracy (Weidmann, 2015, 2014). Weidmann’s study of the accuracy of media-based conflict event data confirmed “the expectation that events with a low number of observers tend to have higher reporting inaccuracies” (Weidmann, 2015: 1129).

Another study confirmed the media’s tendency to systematically underreport or over-report certain types of events. Baum, Zhukov, and Weidmann (2015) found that reporting bias depends on how news organizations navigate the political environment. In democratic regimes, news reporting reflected a preference toward “traditional journalistic standards of newsworthiness to maximize audience attention and revenue” and a pro-challenger bias (Ibid., 387). In non-democracies, the bias was toward reporting with a clear pro-incumbency view, with underreported protests and nonviolent collective action by regime opponents, while largely ignoring government atrocities (Ibid., 397). These types of biases are not just limited to the media, however, and they can also affect development, government and nongovernmental organizations that are increasingly collecting conflict data around the world.

Recent improvements in data collection techniques and increases in the number of agencies collecting localized or disaggregated conflict events data have helped track violent events as well as nonviolent events (Demarest and Lange,r 2018). These agencies use publicly available sources such as news media reports to compile information on different types of conflict events. The two leading large-scale data-collection projects are the UCDP Georeferenced Events Database (UCDP GED) and Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). It is worth noting these two sources have different strengths and focuses.

An important difference among conflict databases is what constitutes a conflict event. This in turn shapes how collected data is coded. UCDP restricts its domain to events that result in at least one fatality while ACLED includes fatal, non-fatal, and nonviolent events (arrests, troop movements, and demonstrations, for instance). One comparative study notes that those interested in nonviolent events only have ACLED to choose from, given that UCDP does not code such data (Eck, 2012: 126). Eck (2012) argues that the limitation of ACLED is its reliance on events (violent or nonviolent) as a unit of analysis, whereas researchers “rarely theorize about events…rather the production and targets of violence” (Ibid). The UCDP GED also uses an “event” as its selector, namely an instance of fatal organized violence as a unit of analysis (Williams, 2017). Eck claims that ACLED’s lack of any assessment of the nature, severity, or intensity of violence means that, for instance, a case like the massacre at Srebrenica is given the “same weight in the database as a sniper attack in Sarajevo” (Eck, 2012: 126). She criticizes ACLED for not providing users with information required to study theories of civil war, including whether the actor is a military or police force, or identifying an actor so that the behavior of a warring party can be analyzed. However, in this study, we were able to collapse the various events into clusters, e.g., violent and nonviolent events, riots and protests based on the classification that the ACLED offers. In other studies, we were able to create other clusters such as government forces, rebel forces, political and ethnic militias, battles or violence committed against civilians (De Waal, 2007; Zambakari, Kang, and Sanders, 2018).

IV. Method

We analyzed data for Somalia from the ACLED Project for 2007 through 2017, including the number of events, the type of events, and fatalities from such events. For those years, the ACLED collected the “types of violence,” agents, dates, and locations of political violence and protest (Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, n.d.). These data are based on several secondary sources, including local and regional news sources, the Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN), Relief Web, Factiva, and various humanitarian agencies (Raleigh et al., 2010, 656).

An event was defined in the ACLED codebook according to several different components: location, actor type, event type, event date, and several other variables (Raleigh and Dowd, 2016). That is, an event is an incident that occurs between designated actors, at a specific named location and on a specific day (date) (Raleigh et al., 2010: 655). An event is defined as an interaction involving at least two actors (Ibid.). For example, an interaction can consist of skirmish or battle between Al-Shabab and Somali government forces. A data entry for a specific event includes the description of the event, the number of fatalities, and several other variables.

In the ACLED database, actors are defined as a group, such as a government entity or a rebel force, but actor types are not mutually exclusive. Even though the ACLED is useful because it provides data about actors in Somalia, it has some limitations (Raleigh and Dowd, 2016). First, due to the security situation in Somalia, it is possible that some events are unreported and hence unrecorded. Secondly, no direct causal relationship can be determined between the event and location or date when it occurred because the study was designed as a descriptive study. Finally, because the ACLED databases rely heavily on media sources, the data used for the study may be biased, resulting in greater measurement error.

Despite these limitations, ACLED offers a comprehensive database that contains incidents of political violence in Africa with a specific focus on tracking the activities of armed and unarmed actors. ACLED works

through local partnerships with Somalia’s “Local Source Project” to maintain access to a network of local Somali reporters who release daily information on the status of political (in)stability in the country. ACLED’s ability to work through partner organizations on the ground improves the quality of the data collected by the agency and its access to the field where data are collected. ACLED also covers a wider range of events than other databases: it compiles information from over 50 sources, more than many of its competitors. Like the UCPD database, ACLED also records one-sided violence toward civilians by both government or rebel actors as well as conflicts between rebel groups.

The ACLED Project collects data on nine different types of events that are political in nature (see Table 1 for descriptions) (Ibid.). For purposes of analysis, the nine categories of events were collated into three event types: violent events, riots and protests, and nonviolent events. See Table 1 for further details on the event types we investigated.

Using the coding rules in the codebook, multiple events that occur on the same day may be coded as a single event, although events that involve the same location on the same day may also be coded separately. If, for example, rebels launched missiles at a government barracks and later that day the government took over the rebel compound that launched the attack, the first event would be coded “remote violence” whereas the second event would be labeled “battle –government regains territory” (Ibid.). Although an incident may have the same date and location, it could have been coded by ACLED as multiple events. In addition, these similar events could have redundant or repeated information, such as fatalities, which consequently would inflate the numbers. To mitigate this, events with the same date and same latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates were collapsed in the same event for this study. Instead of computing the sum of the fatalities, the average was computed across multiple events before they were collapsed.

Death rates were calculated for each administrative region and annually for the whole country: These death rates (per 100,000) were computed by dividing the number of fatalities by 2014 population estimates for whole country as well as yearly estimates for each region (United Nations Population Fund and Federal Republic of Somalia, 2014). In this study, we used the “Population Estimation Survey 2014 for the 18 pre-war regions of Somalia,” the first comprehensive estimation of the Somali population in over four decades conducted by The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and The Federal Republic of Somalia. The survey collected information from 250,000 households in urban, rural, and nomadic settings and camps for the internally displaced people (Ibid.). Our analyses of the ACLED data focused on event type, number of events, and fatalities. The analysis was conducted on data for all 18 administrative regions within Somalia. For yearly estimates, death rates were computed by dividing the number of fatalities by yearly population estimates.

This study sought to investigate violent events, nonviolent events, and events characterized by riots and protests in Somalia between 2007 and 2017 by analyzing ACLED data. We examined the percent distribution of the types of events and types of actors. We investigated the geographic distribution of all events and death rates by region, as well as geographic locations of only violent events. In addition, we longitudinally examined death rates across an 11-year period (2007-2017).

V. Results

Descriptive statistics for the number of political and military events as well as death rates for the country’s administrative regions across an 11-year period were examined. We report the frequency and percent distributions of types of event and actors. Moreover, we report the geographic regions’ distributions first for all events and then for only violent events. Finally, we report annual fluctuations of political and military events across the 11-year period.

Event and actor types:

Analysis of ACLED data indicated that violent events were the most common type of event reported in the database (N = 17,539, 86.87%). About 6.8% of events were nonviolent (N = 1,372) and 6.3% of the events were riots and protests.

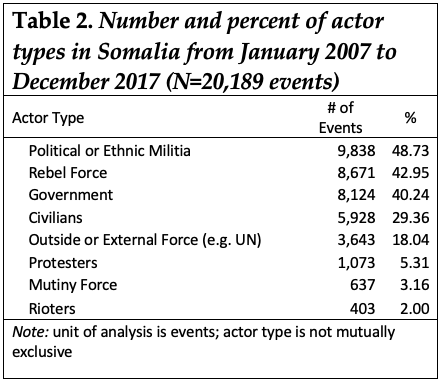

Table 2 summarizes the number of political and military events for each actor type.[1] The percent of actor types is displayed graphically in Figure 1. The actors were primarily political and government entities, ethnic militia and rebel forces. Political or ethnic militias were involved in 48.73% of the events, rebels were participants in 42.95%, and government forces in 40.24% of all events. About 29.36% of the events involved civilians.

Figure 1. Percent of actor types in Somalia (N = 20,189 events)

Regional distribution of all events:

Table 3 contains the number of political and military events, as well as the fatality rates per 100,000 people that were computed by dividing the number of fatalities by population estimates. There were estimated 33,649 fatalities for 20,189 events that occurred in Somalia during the 11-year period. The number of events that occurred in each administrative region ranged between 172 and 6,085. The death rate ranged from three to 738 deaths per 100,000 people.

The number of political and military events as well as death rate for each region is displayed in the maps in Figure 2. Based on the number of events reported in the ACLED database, all the regions with more than 1,000 political and military events were located in the southern part of the country, while all but one of the regions with less than 500 events were located in Somalia’s northern region.

There is a similar regional pattern for fatalities. The death rate for the period 2007-2017 is higher in the southern regions than the northern regions (see Panel B). The five regions with death rates higher than 300 per 100,000 are all located in the southern region of Somalia.

Figure 2. Number of events and fatalities for each region of Somalia between 2007 and 2017. Data Source: Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (N = 20,189 events). Regional boundaries and names do not imply endorsement by the authors or GPPR.

Regional distribution of violent events:

Nonviolent events, as well as riots and protests, appeared to have occurred across the entire country. Because these types of events occurred at lower frequency, the number of events, deaths and death rates were recomputed for violent events (see Table 4).

The four regions with the highest number of violent events and fatalities – Banaadir, Shabeellaha Hoose Bay and Jubbada Hoose – had 5,716 violent events and 9,594 deaths, 2,798 events and 4,303 deaths, 1,316 events and 2,643 deaths, and 1,254 events and 3599 deaths, respectively. Death rates are the same for violent and all events (see Figure 3). The region with the highest death rate was Jubbada Hoose (736 deaths per 100,000). Four additional regions, Banaadir, Gedo, Hiiraan and Bakool, had death rates greater than 400 per 100,000.

The ACLED database contained the location of all the violent events that are recorded as having occurred in Somalia, which made it possible to plot the locations of the violent incidences on a map. The results of this can be seen in Figure 4. Clusters of violent events appeared to have occurred in the more densely populated areas of southern Somalia.

Figure 3. Fatality rates per 100,000 for aggregated events (N=20,189) and violent events (N=17,539) for administrative regions.

Figure 4. Number and location of 17,539 violent events. Excludes riots/protests and nonviolent events. Data Source: Armed Conflict Location and Event Data. Regional boundaries and names do not imply endorsement by the authors or GPPR.

Regional distribution of violent events:

Nonviolent events, as well as riots and protests, appeared to have occurred across the entire country. Because these types of events occurred at lower frequency, the number of events, deaths and death rates number of events, deaths and death rates were recomputed for violent events (see Table 4).

The four regions with the highest number of violent events and fatalities – Banaadir, Shabeellaha Hoose Bay and Jubbada Hoose – had 5,716 violent events and 9,594 deaths, 2,798 events and 4,303 deaths, 1,316 events and 2,643 deaths, and 1,254 events and 3599 deaths, respectively. Death rates are the same for violent and all events (see Figure 3). The region with the highest death rate was Jubbada Hoose (736 deaths per 100,000). Four additional regions, Banaadir, Gedo, Hiiraan and Bakool, had death rates greater than 400 per 100,000.

The ACLED database contained the location of all the violent events that are recorded as having occurred in Somalia, which made it possible to plot the locations of the violent incidences on a map. The results of this can be seen in Figure 4. Clusters of violent events appeared to have occurred in the more densely populated areas of southern Somalia.

Events across time:

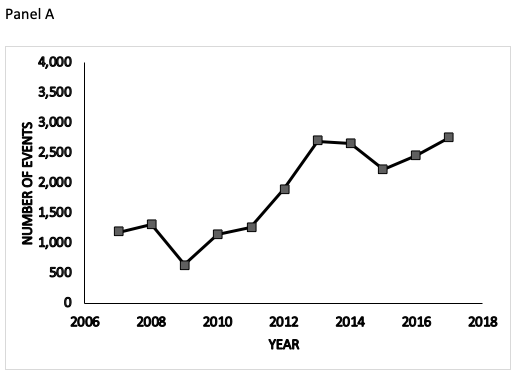

To compare annual fluctuations in violence in Somalia, political and military events were plotted by year from 2007 to 2017 (see panel A of Figure 5). The numbers of political and military events did not change much from one year to another, except for 2009 when there was a 49% decrease. After 2011, however, there was a two-year climb in the number of events before dropping back in 2014 and 2015, and increasing again in 2016 and again in 2017 (albeit at a lower rate of increase than in 2011-2014).

Figure 5. Number of events and fatalities (Panel A) and death rates (Panel B) are plotted as a function of time from 2007 to 2017 (N = 20,189 events).

Death rates from 2007 to 2017 had a pattern of fluctuation from year to year (see Panel B of Figure 5). Death rates remained at the same level between 2007 and 2008, decreased in 2009, and spiked substantially in 2010. From 2009 to 2017, death rates followed the same pattern of decreasing one year and then increasing the following year, with the rates steadily increasing annually until 2017. It should be noted that although the number of violent and military events remained stable after 2013, the fatalities and death rates kept increasing through 2017.

VI. Discussion

In summary, violent events were by far the most common event types. Ethnic and political militia forces were engaged in almost one half of the events, whereas rebel and government forces were each engaged in at least 40% of all events. Moreover, violent events were concentrated in the southern regions of Somalia. There was a surge of fatalities in 2010, and a steady increase in death rate from 2011 until 2017.

Event Types: Riots, protests, and nonviolent events account for a low proportion (13%) of political and military events. Violent events (86.9%) were the most common types in the 11-year period. These consist of remote violence (e.g., long-range missiles or IEDs), violence against civilians (e.g., pillaging or rape), and battles involving seizing territories.

Actor Types: Ethnic and political militant forces were engaged in almost half of the events, whereas rebel and government forces were each engaged in at least 40% of all events. Given the political and military nature of the events reported in the ACLED database, it is not surprising that the majority of actors were political, military, government, or rebel entities.

Regional distribution of violence: There were more political and military events, as well as higher death rates, in southern Somalia than in the northern regions. The Banaadir Region in southeastern Somalia had the highest number of events, is one of the smallest and most densely populated areas, and contains Mogadishu, Somalia’s capital. Similarly, violent events were concentrated in more populated areas of the southern regions of Somalia and along the Shebelle River, which divides the regions of Hiraan, Middle Shabell and Lower Shabelle, and is near the cities of Oddur or Xuddur (south western Bakool region) and Baldoa (capital of the southwestern Bay region). These two towns experienced a combination of the worst drought in 40 years, conflict-induced displacement of civilians, and were battlegrounds between the TFG and the various rebel groups between 2007 and 2017.

Annual fluctuations: Between 2007 and 2011, the numbers of all events did not change much from one year to another, except for 2009, when there was a sharp decrease. After 2011, however, there was a two-year climb in the number of events before somewhat stabilizing from 2014 to 2017. Although the number of events had a moderate increase from 2009 to 2010, there was a sharp increase in death rates in the same time period. Though the number of events remained stable after 2013, death rates kept increasing through 2017.

VII. Conclusion

Several events contributed to the level of fatalities between 2007 and 2017. These included military operations by U.N.-AU forces to drive Al-Shabab out of Mogadishu in 2010, fighting between rival armed groups like Hizbul Islam and Ahlu Sunna Waljama’a outside the capital, Kenyan military intervention in 2011, and the TFG and its allies taking over the port city of Kismayo in 2012 (Human Rights Watch 2010).

Al-Shabab has been determined to expel foreign forces from Somalia. When Ethiopia pulled its forces out in 2009 ahead of the U.N.-backed agreement between the TFG and the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia (ARS), the group turned to fighting the TFG and AMISOM troops. In addition to fighting at home, the group also managed to carry out high-profile attacks in the region: The double bombing of an Ethiopian restaurant and a rugby club in Uganda (2010), the attack on the Westgate mall in Kenya (2013), the attack on Kenya’s Garissa University College (2015), and a more recent attack at a Nairobi luxury hotel complex (2019). The attacks in Uganda and later in Kenya were designed to force Ugandan and Kenyan troops’ withdrawal from Somalia (Sevenzo, Karimi, and Smith-Spark 2019; Stanford University 2016).

The general geographic distribution of events is not a surprise, given the comparative stability in Somaliland and Puntland. However, the increasing levels of violence and rising casualties in central and southern Somalia raise serious questions about the international strategy in Somalia and the various military interventions by regional countries.

The challenge in Somalia is how to stabilize the country and form a government of national unity with buy-in among the warring factions. Political initiatives that emphasize a workable balance through inclusive processes are needed to make sure any new government has sufficient resources and capacity to manage a transition. Furthermore, state legitimization and capacity, building trust among political adversaries, and ensuring the security of the populace require knowledge of the local context and sound judgment in order to offer the best prospects for peace (Call 2008).

Any effort to stabilize Somalia must closely examine the heavy emphasis on the reconstruction of a centralized state, the top-down technical exercise in institution building, and a focus on an externally-imposed peace. Diplomacy and a broad-based political strategy must focus and prioritize civil engagement with key Somali stakeholders and not just military elites. Other countries’ single-minded focus on weakening Al-Shabab’s fighting capacity must be balanced with a more pragmatic approach to open dialogue with all key stakeholders. Any dialogue must balance what the Somali people want versus the interests of Britain, the United States, France, or regional powers, such as Kenya and Ethiopia.

In lineage-based Somalia, where clans define social relations, working with clan and religious leaders can be another effective approach to preventing violence and providing a traditional method of conflict management for clans. Clan identity also serves as a functional mechanism for the collective organization of economic interests in the pursuit of state access and control of political power (Ibid., 235).

Paradoxically, the only recent example of an alternative to external intervention in Somalia was the Islamic Courts movement (in 2006) that organized the merchant class (Ibid.). This effort was driven by the interests of the Mogadishu business class. Unfortunately, local Somali hostility toward the Islamic Courts Union and internal challenges forced it to dissolve. However, it offered an alternative model for stabilizing Somalia by uniting different strata of the business class around common interests (Ibid., 236).

The United States’ sole focus on security in Somalia comes at the expense of nation-building activities, development efforts, and democratic peace building activities between and within warring clans (Suri, 2016: 42). Repressive counterinsurgency, conducted largely by external actors, has been counterproductive and reactive, lacking in both inclusive approaches to resolving conflict and a shared political strategy supported by intervening actors in Somalia. The stabilization of Somalia is in the long-term interest of the region (stability, democratization and development), the United States (regional security and trading route), and the European Union (forced displacement and migrants). Furthermore, the geopolitical consequences of a protracted conflict in Somalia has detrimental effects on Somalia, the Horn of Africa, and the maritime traffic from the Gulf of Aden to the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean.

Given that Somalia’s conflict has multiple dimensions and is at local, national, regional, and international levels, sustainable peace and stability will require a long-term political strategy. This strategy should address governance deficits and establish stability by including local and regional stakeholders and international guarantors. In the absence of a decisive military victory over insurgents, it may be realistic to open dialogue with all the armed insurgents, including Al-Shabab, while supporting reconciliation between other armed and unarmed groups. This will require working with local organizations, cross-clan associations such as civil society organizations (CSOs), and cross-clan businesses in the private sector to work as potential partners in efforts to promote peace in Somalia.

+ Author biographies

Christopher D. Zambakari, MBA, MIS, LP.D., is the CEO of The Zambakari Advisory.

Richard Rivera (MA), Statistician & Psychometrician, The Zambakari Advisory.

+ Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Michael Summerton, Dr. Margaret Camarena, Matthew Edwards, Kyle Anderson, Jinzhou Zhang, Cleophus Thomas III, and consultants at The Zambakari Advisory, the anonymous reviewers and members of the Editorial Team for The Georgetown Public Policy Review for their contributions and readings of earlier drafts of the manuscript.

+ Footnotes

[1] The type of actor is not mutually exclusive because an event could consist of multiple actors.

+ References

ACLED. "Methodology." Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, http://www.acleddata.com/methodology/.

Africa ResearchBulletin. "Full Issue." Africa Research Bulletin: Political, Social and Cultural Series 47, no. 9 (2010/10/01 2010): I-I."Al Shabaab." Stanford University, https://web.stanford.edu/group/mappingmilitants/cgi-bin/groups/view/61.

Anderson, Mark "Somalia: How to Build Hope Amid the Horror of Al-Shabaab's Insurgency." The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/jan/04/somalia-al-shabaab-insurgency-mogadishu-mohamed-nur.

Baum, Matthew A., Yuri M. Zhukov, and Nils B. Weidmann. "Filtering Revolution." Journal of Peace Research 52, no. 3 (2015): 384-400.

Call, Charles. "Building States to Build Peace? A Critical Analysis." Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 4, no. 2 (2008): 60.

Collier, Paul, and Anke Hoeffler. "On Economic Causes of Civil War." Oxford Economic Papers 50, no. 4 (1998): 563-73.

De Waal, Alex. "Class and Power in a Stateless Somalia." The Social Science Research Council (SSRC), http://hornofafrica.ssrc.org/dewaal/printable.html, 2007.

———. "Getting Somalia Right This Time." International Herald Tribune 22 Feb. 2012.

De Waal, Alex. "Getting Somalia Right This Time." International Herald Tribune 22 Feb. 2012.

Demarest, Leila, and Arnim Langer. "The Study of Violence and Social Unrest in Africa: A Comparative Analysis of Three Conflict Event Datasets." African Affairs 117, no. 467 (2018): 310-25.

Eck, Kristine. "In Data We Trust? A Comparison of Ucdp Ged and Acled Conflict Events Datasets." Cooperation and Conflict 47, no. 1 (2012): 124-41.

Elliot, Ashley, and Georg-Sebastian Holzer. "The Invention of ‘Terrorism’ in Somalia: Paradigms and Policy in Us Foreign Relations." South African Journal of International Affairs 16, no. 2 (2009/08/01 2009): 215-44.

Escobar, Pepe. "The African 'Star Wars'." Al Jazeera English, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2011/04/2011422131911465794.html.

Fearon, James D., and David D. Laitin. "Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War." The American Political Science Review 97, no. 1 (2003): 75-90.

Hagmann, Tobias "Stabilization, Extraversion and Political Settlements in Somalia." Londong, UK/Nairobi, Kenya: The Rift Valley Institute, 2016

Harsch, Michael F. . "A Better Approach to Statebuilding: Lessons from "Islands of Stability"." Foreign Affairs, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2017-01-02/better-approach-statebuilding?cid=nlc-fatoday-20170102&sp_mid=53113296&sp_rid=Y2hyaXN0b3Bob3JvMjAwMkBnbWFpbC5jb20S1&spMailingID=53113296&spUserID=MjA5NDMyODc3MTIzS0&spJobID=1080302817&spReportId=MTA4MDMwMjgxNwS2.

Hesse, Brian. "Two Generations, Two Interventions in One of the World’s Most-Failed States: The United States, Kenya and Ethiopia in Somalia." Journal of Asian and African Studies 51, no. 5 (2016/10/01 2014): 573-93.

———. "Why Deploy to Somalia? Understanding Six African Countries’ Reasons for Sending Soldiers to One of the World’s Most Failed States." The Journal of the Middle East and Africa 6, no. 3-4 (2015): 329-52.

Hirsch, John L. "Peacemaking in Somalia: Au and Un Peace Operations." In The Palgrave Handbook of Peacebuilding in Africa, edited by Tony Karbo and Kudrat Virk, 137-51. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018.

Human Rights Watch. "Harsh War, Harsh Peace." New York: Human Rights Watch. Accessible from https://www.hrw.org/report/2010/04/19/harsh-war-harsh-peace/abuses-al-shabaab-transitional-federal-government-and-amisom, 2010.

Ibrahim, Mohamed. "Somalia and Global Terrorism: A Growing Connection?". Journal of Contemporary African Studies 28, no. 3 (2010/07/01 2010): 283-95.

Ingiriis, Mohamed Haji. "The Invention of Al-Shabaab in Somalia: Emulating the Anti-Colonial Dervishes Movement." African Affairs 117, no. 467 (2018): 217-37.

Kishi, Roudabeh. "Violence in Somalia." Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), http://www.crisis.acleddata.com/violence-in-somalia/.

Malito, Debora Valentina. "Building Terror While Fighting Enemies: How the Global War on Terror Deepened the Crisis in Somalia." Third World Quarterly 36, no. 10 (2015): 1866-86.

———. "Neutral in Favour of Whom? The Un Intervention in Somalia and the Somaliland Peace Process." International Peacekeeping (2016): 1-24.

McGowan, Patrick J. "Coups and Conflict in West Africa, 1955-2004." Armed forces and society 32, no. 2 (2006): 234-53.

Menkhaus, Ken. "Chapter 3: Somalia, Global Security and the War on Terrorism." The Adelphi Papers 44, no. 364 (2004/04/01 2004): 49-75.

———. "The Crisis in Somalia: Tragedy in Five Acts." African Affairs 106, no. 424 (2007): 357-90.

———. "State Collapse in Somalia: Second Thoughts." Review of African Political Economy 30, no. 97 (2003): 405-22.

Messner, J. J. , Nate Haken, Krista Hendry, Patricia Taft, Kendall Lawrence, Laura Brisard, and Felipe Umaña. Failed States Index 2014: The Book. Washington, D.C.: The Fund for Peace, 2014.

Price, Megan, and Patrick Ball. "Big Data, Selection Bias, and the Statistical Patterns of Mortality in Conflict." The SAIS Review of International Affairs 34, no. 1 (2014): 9-20.

Raleigh, Clionadh, and Caitriona Dowd. "Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (Acled) Codebook 2016." Sun Prairie, WI/Austin, TX: Accessible from

Raleigh, Clionadh, Andrew Linke, Håvard Hegre, and Joakim Karlsen. "Introducing Acled: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset: Special Data Feature." Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 651-60.

Richmond, Oliver P. "Failed Statebuilding Versus Peace Formation." Cooperation and Conflict 48, no. 3 (September 1, 2013 2013): 378-400.

Roitsch, Paul E. "The Next Step in Somalia: Exploiting Victory, Post-Mogadishu." African Security Review 23, no. 1 (2014/01/02 2014): 3-16.

Schrodt, Philip A. "Precedents, Progress, and Prospects in Political Event Data." International Interactions 38, no. 4 (2012/09/01 2012): 546-69. Sevenzo, Farai, Faith Karimi, and Laura Smith-Spark. “At Least 21 Killed as Kenya Hotel Seige is Declared.” CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/16/africa/kenya-hotel-complex-terror-attack/index.html.

Suri, Sunil. ""Barbed Wire on Our Heads": Lessons from Counter-Terror, Stabilisation and Statebuilding in Somalia." London, UK: Saferworld. Accessible from https://www.saferworld.org.uk/resources/publications/1032, 2016.

The Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP). "Global Peace Index 2016 ". Sydney, New York and Mexico City: Accessible from

UNFPA, and The Federal Republic of Somalia. "Population Estimation Survey 2014 for the 18 Pre-War Regions of Somalia." Nairobi, Kenya. Accessible from https://www.unicef.org/somalia/media_16551.html: United Nations Population Fund & The Federal Republic of Somalia. , 2014.

United Nations Security Council. "Unanimously Adopting Resolution 2431 (2018), Security Council Extends Mandate of African Union Mission in Somalia, Authorizes Troop Reduction." United Nations Security Council, https://www.un.org/press/en/2018/sc13439.doc.htm.

Vidino, Lorenzo, Raffaello Pantucci, and Evan Kohlmann. "Bringing Global Jihad to the Horn of Africa: Al Shabaab, Western Fighters, and the Sacralization of the Somali Conflict." African Security 3, no. 4 (2010/11/29 2010): 216-38.

Weidmann, Nils B. "A Closer Look at Reporting Bias in Conflict Event Data." American Journal of Political Science 60, no. 1 (2016): 206-18.

———. "On the Accuracy of Media-Based Conflict Event Data." Journal of Conflict Resolution 59, no. 6 (2015): 1129-49.

Williams, Paul D. . "A Navy Seal Was Killed in Somalia. Here’s What You Need to Know About U.S. Operations There." The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/05/08/a-navy-seal-was-killed-in-somalia-heres-what-you-need-to-know-about-u-s-operations-there/?utm_term=.adec28effb50.

World Bank. "Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics ". Washington, DC.: World Bank. Accessible from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/8476, 2005.

Zambakari, Christopher, Tarnjeet K. Kang, and Robert A. Sanders. "The Role of the Un Mission in South Sudan (Unmiss) in Protecting Civilians." Chap. 5 In The Challenge of Governance in South Sudan: Corruption, Peacebuilding, and Foreign Intervention, edited by Steven C. Roach and Derrick K. Hudson. London, New York: Routledge, 2018.